Article from the October 2022 Newsletter. Would you like to receive it by e-mail? Join Muses & A.R.T.!

Or request it via our contact form!

[Information taken mainly from the french Encyclopedia Universalis and François Debiesse’s french book Le Mécénat (see Sources) ; article translated from french with deepl.com].

« Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people have provided to artists such as musicians, painters, and sculptors»

(definition on Wikipedia)

« Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people have provided to artists such as musicians, painters, and sculptors »

(definition on Wikipedia)

« A patron is a person who supports and gives money to artists, writers, or musicians. […] »

(definition on Collinsdictionnary.com)

« A patron is a person who supports and gives money to artists, writers, or musicians. […] »

(definition on Collinsdictionnary.com)

Patronage has shaped the art world since antiquity. Whether as patrons of artists, wealthy sponsors or simple lovers of the arts and letters, patrons have always encouraged art with their wealth and influenced its development in our societies.

Here, we sketch out a brief history of artistic patronage spanning almost 2,500 years, through illustrious figures from Pericles to Peggy Guggenheim, via Charlemagne, Isabella of Bavaria and the Medici, colorful personalities who left their mark on the history of Western art and that of their era.

At the beginning…

« Mécène, issu d’aïeux rois, ô toi mon appui et ma douce gloire […] si tu me donnes une place parmi les lyriques inspirés, j’irai, au haut des airs, toucher les astres de ma tête. »

(Horace, Odes, I, 1 ; Traduction de François Villeneuve, Les Belles Lettres, 2002)

« Caius Cilnius Maecenas ».

Three words for a great name from Ancient Rome, Frenchized as “Mécène“. This is the origin of the common names “mécène” and “mécénat” in french langage, translated by “patron” and “patronage” in english.

So who was this great figure, often overlooked by the general public?

We’re in the midst of a civil war in the middle of the 1st century BC, in the troubled period of the Roman Triumvirate, following the assassination of Caesar. A political figure, a knight and a man of great diplomacy and wealth, Maecenas showed great influence with his friend Octavian before the latter became Emperor Augustus. He played an important political role, helping Octavian to found his Empire and restore the Republic. Our official sources of the time are silent on his political life. Despite his power, Maecenas rejected honors and never became a senator under Augustus. He chose to remain in the shadows, while continuing to exert his influence on the new Emperor and his dynasty.

Maecenas (Mécène) is best remembered for his love of the arts and literature, and the protection he gave to illustrious poets. Our sources on this subject are Virgil, Horace and Propertius, who often praised their protector in their writings, without any quid pro quo. Maecenas entertained poets and musicians in his gardens at lavish banquets, which our authors will not fail to recount. No propaganda about the reign of Octavian, then Augustus, or the political and military life of his time was imposed on these men of letters, these friends whose songs he encouraged. Maecenas loved and supported poets, and gave them complete freedom in their art.

The firsts patrons...

Artistic creation seen as a “symbol of power and worship” gave rise to the first patrons among kings and priests.

In ancient Egypt, the construction of the pyramids reflected the power of the pharaohs. In Greece, art became a symbol of the greatness of the “enlightened tyrants” of the time, to the detriment of the artist, a mere anonymous craftsman, as in the “century of Pericles” (5th c. BC), which saw the birth of the Acropolis and the Parthenon in Athens. The first collections of precious objects, or “treasures” (the first votive offerings), were found in ancient temples such as Olympus and Delphi in the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

Ptolemy, as king and former general of Alexander the Great (himself a great patron of the arts), was responsible for the construction of the Museion, a free university for scholars, and of the famous Library of Alexandria in 288 BC, two landmarks of the Hellenistic period. The first private collections of statues and bronzes, and even the first private pinacotheques (picture galleries), were created in Rome as a result of wartime looting as early as the 3rd century BC. Roman emperors, such as Augustus and Nero, also became patrons of the arts, building great structures to consolidate their domination.

While patronage as we understand it today was mainly concerned with poets and writers at the time, with artists having only the status of anonymous craftsmen, the rulers of Antiquity left behind, through these nameless creators, a collection of works of art and majestic edifices built in their names.

Religious patronage... and also secular !

In the early Middle Ages, with the arrival of Christianity, so-called “criminal” pagan art came under attack, and a great loss of the artistic heritage of antiquity was deplored.

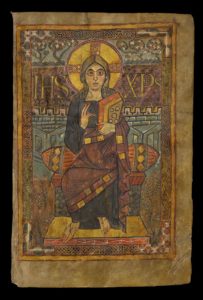

While secular art disappeared, a new Christian art developed with the “cult of sacred images”. Private patronage and individual collections were replaced by religious patronage. Works of art were created by the monks themselves, and assembled in churches and monasteries (illuminated manuscripts, ex-votos, etc.). Monks became builders, like the Benedictines in the 11th century and the Cistercians in the 12th.

Among the great patrons of the period was Abbot Didier of Mont Cassin in Italy (1023-1087), the future Pope Victor III, who promoted manuscript copying and illumination, notably by importing miniature manuscripts from the East. The abbot Suger of Saint-Denis (1081-1151) is also remembered as one of the precursors of the new Gothic art, of which the famous “Saint-Denis” abbey and its many innovations (architecture, goldsmithing, stained glass, etc.) became the model.

Sovereigns also became patrons of the arts. Among them was Emperor Charlemagne, patron of the arts and letters, and originator of the “Carolingian Renaissance or Reform” (768-877), in which culture and learning were given pride of place. In addition to an undeniable love of art, here again venality, ambition and imperialism animated the hearts of our new patrons. And courtiers and knights soon followed in their sovereigns’ footsteps.

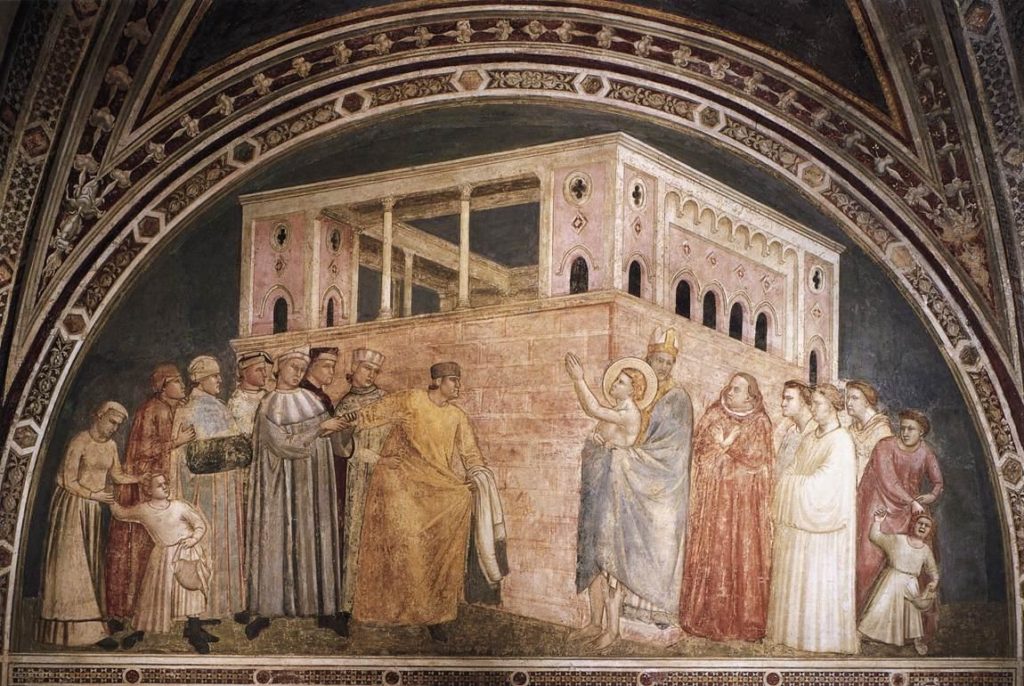

In the Gothic period, in addition to the patronage of clerics and kings, a more secular and bourgeois patronage appeared, with the construction and luxurious ornamentation of castles, palaces and other residences. Giotto (1266/67-1337) was commissioned by wealthy Italian banking families such as the Peruzzi and Bardis, for whom he created a series of frescoes in their respective chapels in Florence’s Basilica Santa Croce. Private collections were reborn with a new aesthetic, such as those of the Duke of Burgundy (Philippe II Le Hardi, 1348-1404) and those of his brother Duke Jean de Berry (1340-1416), built up primarily out of passion and for their own personal pleasure.

The splendor of Princes... and princesses!

The patronage of medieval princesses and their descendants

[The informations in this sub-section are from the french book « La Dame de Cœur », Patronage et mécénat religieux des femmes de pouvoir dans l’Europe des XIVe-XVIIe siècles, (see Sources)]

Although historians of patronage have often been coy about the existence of female patrons, there are plenty of them! The 21st century is tending to rehabilitate them, and many texts today cite them as examples. The influence of women patrons can be traced back to at least the end of the Middle Ages (13th-14th centuries), when the documentary revolution provided us with numerous written sources, such as collection inventories and accounting reports describing the purchases made by kings, princes… and queens!

« Ces princesses sans souveraineté efficiente ne sont ni sans pouvoir, ni sans ambition, et leur capacité à valoriser leurs apports dans l’affirmation dynastique des pratiques de mécénat et de dévotion en porte témoignage. »

(Fanny Cosandey, dans « La dame de cœur », Patronage et mécénat religieux des femmes de pouvoir dans l’Europe des XIVe-XVIIe siècles, 2016)

« Ces princesses sans souveraineté efficiente ne sont ni sans pouvoir, ni sans ambition, et leur capacité à valoriser leurs apports dans l’affirmation dynastique des pratiques de mécénat et de dévotion en porte témoignage. »

(Fanny Cosandey, dans « La dame de cœur », Patronage et mécénat religieux des femmes de pouvoir dans l’Europe des XIVe-XVIIe siècles, 2016)

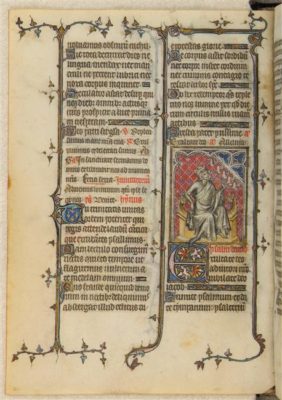

Although their power as women was limited, consort queens were nonetheless influential in areas such as religious patronage and patronage of the arts. In such cases, we speak of a “complementarity of powers” with the king. As “Patrons of the Arts and Letters”, they commissioned artists and craftsmen, enabling the acquisition of numerous works of art (altarpieces, paintings, silverware, etc.), literature and religion, as well as architecture. Their exemplary piety and charity led them to found churches, convents, monasteries and hospitals, both theologically and politically. Greatly cultivated readers, they encouraged literary creation and the translation or copying of ancient manuscripts, and created libraries, such as that of Charlotte of Savoy (1441-1483) in Bourges, which included a number of works commissioned from the illuminator Jean Colombe.

As “guardians of memory”, they are responsible for the “salvation of the souls of their parents and spouses”. To this end, they enriched the funerary heritage with artistic commissions featuring themselves and their deceased loved ones, for example. Thus, in 1353, Jeanne d’Evreux (1310-1371) was one of the first to have herself and her deceased husband, the Capetian King Charles IV, depicted in statues on the portal of the Grands Carmes church in Paris, the construction of which she had partly financed (now no longer in existence). For Mahaut d’Artois (1269/70-1329), commissioning sumptuous tombs not only glorified the deceased, but also the Capetian dynasty and legitimized her lineage, both religiously and politically.

One of the most important expressions of the queen’s religious patronage is her chapel. Like the king and other reigning princes of medieval times, queens, princesses and duchesses each had their own autonomous “hotel” or “house”, which made up their entire official entourage, from their personal court to the members administering the various trades (kitchen, scullery, stables, etc.) and rooms, including the chapel. The “Queen’s Chapel”, in the effigy of the King’s but smaller in size, is a geographical space within the Palace, with all the clerks surrounding the Queen, as well as all the objects making up the “sacred treasure” (goldsmiths, tapestries, books, liturgical objects and vestments, reliquaries…). Created for the needs of the Court, the chapel became “the public setting for a private devotion”.

The royal written sources surrounding the chapel of Isabella of Bavaria (1370-1435) provide us today with a fine example of how a female chapel functioned. Over the centuries, Isabella of Bavaria has been unjustly known by the first name “Isabeau”, a “familiar and disparaging nickname” designed to discredit the queen, and which first appeared in the writings of a chronicler at the very beginning of the 15th century. As early as 1393, when her husband King Charles VI, known as “Le Fou”, was suffering from a fit of madness, she was granted power and financial autonomy, as well as a certain place in the royal archives. Her chapel was adorned with luxurious objects and colors, in a splendor that supplanted that of the king and made it one of the most striking in the West, contributing to the queen’s “black legend”. It was also one of the first to host a “musical chapel”, where famous polyphonic music was performed by the finest singers. Accounting records show the purchase of several organs to equip her chapel. Marie d’Anjou (1404-1464) and Anne de Bretagne (1477-1514) followed her symphonic example.

The queen saw herself as a model of Christianity, to be imitated by her subjects. The chapel, used in particular for the celebration of mass, became itinerant, following the queen on her many travels in the form of a portable oratory. The chapel was shown off, showcasing the sovereign’s prestige and inviting her to set an example.

And it is through these women that the memory of certain saints is passed on. Anne de Bretagne (1477-1514) is depicted in her Book of Hours with three saints, including St. Ursula, whose cult she encouraged. The queens of France, descendants of Louis IX (1214-1270), canonized St. Louis in 1297, are at the origin of the “cult of St. Louis”. Mahaut d’Artois, his great-niece, contributed like him to the protection of the Mendicant orders, notably through the foundation of convents and legacies, but also to the dissemination of the memory of the holy king, whose relics she was one of the few, along with Jeanne d’Evreux, to possess. She created liturgical objects in his honor, and dedicated a Book of Hours to him… Clémence de Hongrie (1293-1328), a descendant of the King of Hungary and of the Habsburg lineage, was raised in Naples. By marrying King Louis X Le Hutin, great-grandson of Saint Louis, she became Queen of France, and also helped spread the cult.

The cult of Saint Louis even spread to Spain. The figure of Saint Louis had already been known there since the 13th century, a popularity reinforced by Charles V, who then claimed to be the worthy successor of the holy king. But it was above all with those known as “the queens of peace” that the cult of Saint Louis’ medieval origins developed on the Iberian peninsula. Élisabeth de Valois (1545-1568) and Isabelle de Bourbon (1602-1644) contributed to the stability of political relations between the French and Hispanic monarchies in the 16th and 17th centuries, at a time of Catholic reform, and to the consolidation of lineage and power in the footsteps of their elders. Over the centuries, Spanish royalty appropriated the image of Saint Louis, whose cult and representation strongly influenced Hispanic artistic culture (pious foundations, paintings, translations of texts, etc.).

For her chapel, Eleonora of Sicily (1325-1375), Queen of Aragon, called on artists from a variety of backgrounds, whom she recruited from the Pope in Avignon or from Dukes and Duchesses of other kingdoms. On her journey from the court of Naples to France, Clémence de Hongrie brought back the writings of Dante and Petrarch.

Married into other dynasties or families, queens were mobile, circulating not only their royal lineage and the cultural model from which they sprang, but also their model of devotion and patronage throughout Europe.

The Italian Quattrocento

The princes of the Italian Quattrocento left their mark on the history of art and patronage with their splendor and influence.

The best-known example is the Medici, a wealthy family that protected both the arts of the past and the new. Cosimo first and foremost, but especially Lorenzo the Magnificent, imbued Florence and the whole of Italy with their intellectual aura and taste for aesthetics.

Patron princes had to demonstrate exemplary intellectual activity and artistic culture. Among them were the Montefeltro family of Urbino, such as Federico III, who was a great friend of the humanists, and the Este family of Ferrara and the Visconti family of Milan. They knew how to surround themselves with the best scholars and “artists” within their stately palaces. In Rome, literary academies were founded by wealthy families and influential cardinals, bringing together the cultivated men of the age.

« Il est difficile de savoir qui décide du succès d’un artiste, qui impose ses goûts et ses préférences aux autres commanditaires »

(Michel Hochmann, dans Peintres et commanditaires à Venise (1540-1628), Publications de l’École Française de Rome1992)

« Il est difficile de savoir qui décide du succès d’un artiste, qui impose ses goûts et ses préférences aux autres commanditaires »

(Michel Hochmann, dans Peintres et commanditaires à Venise (1540-1628), Publications de l’École Française de Rome1992)

With Lorenzo de Medici and his contemporaries, the role of the patron unfolds. By means of authentic signed contracts, it is he who finances and decides on the making of a work of art, from its conception to its finality, from its subject to the choice of materials, such as that of color pigments. Ultramarine blue, extracted from lapis lazuli, an expensive pigment coveted by wealthy patrons, was often specified in written contracts to avoid any inferior counterfeits.

« […] ce panneau devra être doré à l’or fin et peint avec des couleurs de qualité, et spécialement avec du bleu d’outremer […]. Et ledit Piero s’est engagé […] à le livrer entièrement assemblé et installé dans un délai de trois ans ; et à ce qu’aucun autre peintre que Piero lui-même ne puisse tenir le pinceau. »

(Extrait du contrat pour la commande de la Vierge de la Miséricorde de Piero della Francesca du 11 juin 1445, par le prieur Pietro Di Luca au nom de la confrérie de Santa Maria della Misericordia, cité par Michael Baxandall dans l’Œil du Quattrocento, p. 33-34, 2020)

« […] ce panneau devra être doré à l’or fin et peint avec des couleurs de qualité, et spécialement avec du bleu d’outremer […]. Et ledit Piero s’est engagé […] à le livrer entièrement assemblé et installé dans un délai de trois ans ; et à ce qu’aucun autre peintre que Piero lui-même ne puisse tenir le pinceau. »

(Extrait du contrat pour la commande de la Vierge de la Miséricorde de Piero della Francesca du 11 juin 1445, par le prieur Pietro Di Luca au nom de la confrérie de Santa Maria della Misericordia, cité par Michael Baxandall dans l’Œil du Quattrocento, p. 33-34, 2020)

The cost of noble materials was replaced by the value of craftsmanship, and painters in particular soon made a name for themselves among these “new patrons”. At the very beginning of the 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo imposed their “creative genius” and played an active role in the conception of their highly prized art.

The model of Italian patronage crossed borders, and sovereigns such as François I (1494-1547) and Charles V (1500-1558) invited renowned Italian painters to their own courts. Leonardo da Vinci, for example, was invited to stay at Le Clos Lucé in the court of François I at the Château d’Amboise.

The kings hired the services of artists who became official court painters, and whom the queens also used at will.

Isabelle d’Este (1474-1539), of humanist culture and education, was appreciated by many of her contemporaries, and was one of the greatest figures of Renaissance artistic patronage. The Marquise of Mantua is famous for her Studiolo and Grotta, rooms in Mantua’s Palazzo Ducale, which house her collections of ancient and modern art, with their wealth of paintings, ancient and contemporary sculpture, marquetry, precious stones, ancient coins… For her commissions, she turned to the most prolific artists of her time, such as Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, Leonardo da Vinci, Perugino, Raphael, Titian, Correggio, Giulio Romano, and of course the court painters Andrea Mantegna and Lorenzo Costa. His library was adorned with numerous works printed by the great Aldo Manuce.

Gorgio Vasari (1511-1574), who founded Florence’s first drawing academy, the Accademia dell’Arte del Disegno, in 1563, built up the city’s first collection of drawings, and was responsible for the construction of the Uffizi, which houses what is considered to be the first true art gallery.

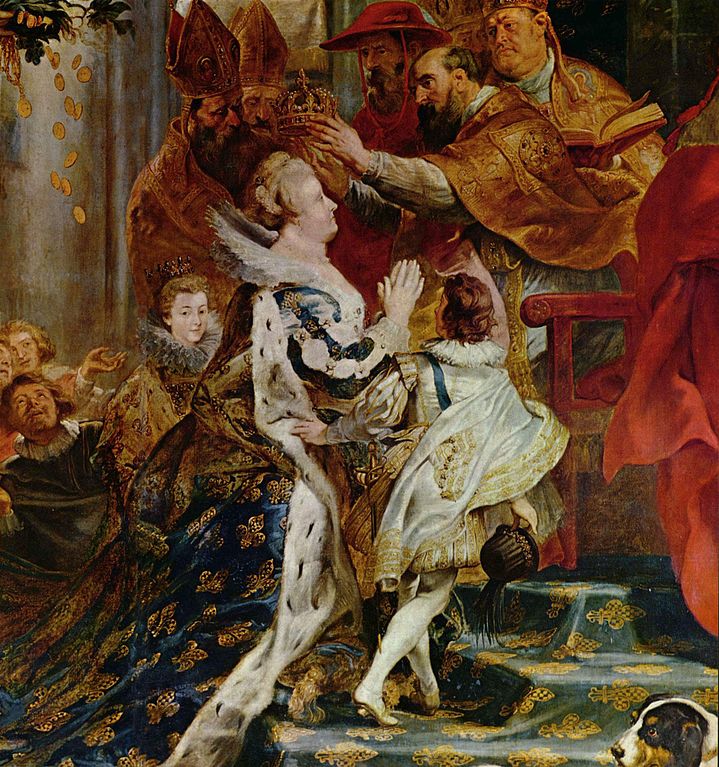

Marie de Medicis (1575-1642), widow of the French king Henri IV, surrounded herself with great artists, and commissioned Rubens, invited to her court for the occasion, to paint a series of pictures for the Palais du Luxembourg in honor of the marriage of one of her daughters. Rubens was a renowned painter whose services were also offered by Isabelle Claire Eugénie (1566-1633), co-sovereign of the Southern Netherlands.

The "bourgeois collections" of the 16th and 17th centuries

Antiquity and modern art drive the acquisitions of these “collectors”. The “buyers”, on the other hand, had a more pronounced taste for contemporary works, which flocked to exhibitions and auctions in the heart of 16th- and 17th-century Flanders and Northern Europe. A “bourgeois” world was awakening, painters were asserting themselves and freeing themselves from princely commissions, patrons were becoming rare, and paintings were finding buyers even from the most modest of backgrounds.

This new fashion spread throughout Europe. Public exhibitions and boutiques abounded in Rome and Venice. The 17th century saw the emergence of the first salons in France under Louis XIV, and the first auctions in England.

In Protestant countries, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation signaled the end of Church commissions in favor of these “bourgeois collections”, while religious orders in Italy and other Catholic countries reinforced the role of the patron, who backed up his authority with greater control over iconography and painters, even to the point of censorship.

Between sovereignty and amateurism...

But the 17th century was also a period of great patronage by popes and kings.

The popes, fervent defenders of Roman tradition, saw art as a means of enhancing the prestige of the capital of the Catholic world. Urban VIII (pope from 1623 to 1644) gloried in the presence of the cavalier Bernini, a coveted sculptor, architect and painter, during his pontificate.

Great kings became great rivals of Rome, such as Louis XIV in France, Philip IV in Spain and Charles I in England. Under the government of Colbert, Louis XIV’s minister, the Académie de France was founded in Rome in 1666, along with the first royal factories. The Sun King even managed to bring Le Bernin to Paris with the consent of Alexander VII (Pope from 1655 to 1667). Art took on a political dimension, and the dictate of “taste” was entrusted to Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), the king’s first painter, who responded to the demands of a reigning monarch as the first artistic “dictator”.

Some patrician families tried to match the sovereigns’ patronage. But it was “bourgeois amateurism” that won over Rome and other major European cities. These included Cassiano Del Pozzo, a great Italian scholar, collector and antiquarian in his spare time, and protector of Nicolas Poussin; Giulio Mancini, an Italian physician, collector, art dealer and writer, who left behind a number of works on contemporary artists; and Giovanni Pietro Bellori, archaeologist, curator of the Antiquities of Rome, historian, art critic and biographer, renowned for his theory of the “ideal beauty”. The number of art dealers multiplied in the service of a painting that was evolving. Painters, such as Nicolas Poussin and Salvator Rosa, rejected official commissions and turned to private individuals to fully express “the freedom of their artistic genius”.

Between decline and renewal...

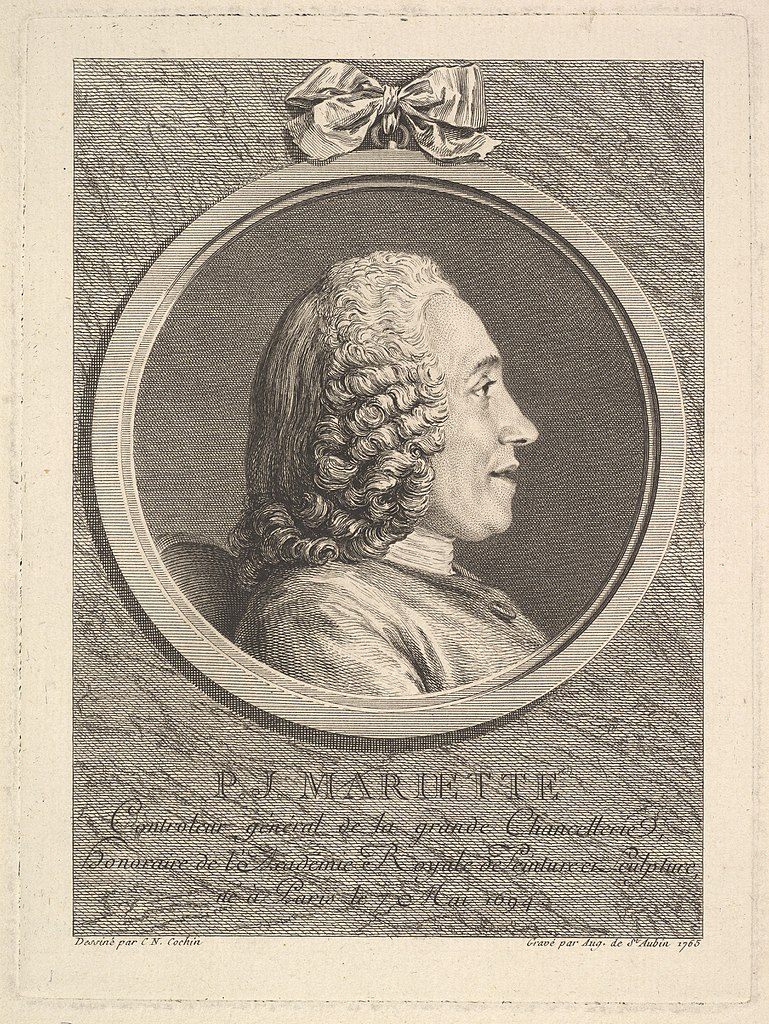

The 18th century saw the decline of traditional patronage in favor of a new fashion in which amateurs and the curious influenced a more societal art that moved away from the splendor of the official court. A “modern art” was born, with an aesthetic that won over not only artists, but also critics and new amateur buyers. Among the patrons of the period, the names of Pierre Crozat and Pierre-Jean Mariette, great collectors, left their mark on history, notably through the publication of collections of engravings featuring the finest works of art, aimed at this new, enlightened public.

Academies, institutes and museums flourished. Florence, Dresden and Kassel became home to national and public museums. Spurred on by the French Revolution, recognition of the public interest of collections led to the establishment of the Louvre as the Republic’s Central Museum of the Arts in 1793. Napoleon‘s victories enriched French collections, which became part of the Musée Central des Arts or Musée Napoléon. The Restoration saw the foundation of public museums with a cultural and educational vocation throughout Europe.

This new era, marked in particular by the crisis of the aristocracy and the importance of museum collections, silenced private patronage in favor of government and public patronage. The state became a sponsor, and commissions were essentially a means for the state to assert its power and glorify its image, with all the constraints that imposed submission on the creative artist.

The industrial revolution brought with it a certain disillusionment: the work of art was industrialized and perceived as a mere “reproducible, commercial object”, losing its usefulness. A rift between artist and patron began to form, prompting the painter Gustave Courbet, the figurehead of the free artist, to say: “I despise patrons”. Artists asserted themselves and became controversial, and were refused entry to official exhibitions.

Finally, after 1870, a form of patronage was reborn, protective and supportive, with dealers at its heart, invested in the future of their artists, for whom they did not hesitate to take risks. Paul Durand-Ruel, for example, supported painters from the Barbizon School and the Impressionists, while Ambroise Vollard revealed the work of Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse, among others.

After the First World War, contemporary art attracted the crowds, and great patrons and collectors re-emerged. They donated their imposing collections of ancient and modern art to the state, which in turn fed public museums. Businesses, sniffing out their own interests, were quick to follow suit and support the arts, which they linked to new market trends through the evolution of fashions and “tastes”.

Some great patrons at the crossroads of the 19th and 20th centuries

Among the great private patrons of the period were Ivan Abramovitch Morozov (1871-1921) and Sergueï Ivanovitch Chtchoukine (1854-1936). These Russian art lovers, particularly of French art, were great collectors of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, as well as works from the Nabis, Fauvist and Cubist movements, and popularized the avant-garde art rejected by their French contemporaries. The turbulent times in Moscow at the beginning of the 20th century forced them to emigrate, and their respective collections were confiscated by the Russian government in 1918 and transformed into national museums.

For her part, Louisine Havemeyer (1855-1929), known for her feminism and, in particular, her campaigning for women’s suffrage, was introduced to art by none other than the American painter Mary Cassat, and played a key role in the rise of Impressionism in the United States. Many pieces from the immense collection she built up first alone, then with her husband, were bequeathed to New York’s Metropilitan Museum of Art (MET) in 1929.

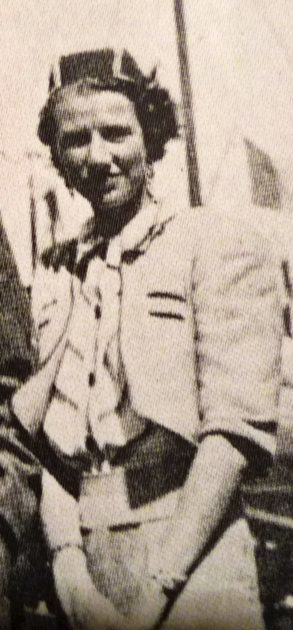

![Photographie de Marie-Louise Peyrat, la Marquise Arconeti-Visconti, dans les années 1900 (Unknown [beginning of 20th c.], Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) histoire mécénat art muses et art](https://www.muses-et-art.org/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Photographie-de-Marie-Louise-Peyrat-la-Marquise-Arconeti-Visconti-dans-les-annees-1900-Unknown-beginning-of-20th-c.-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons-pwduu1vm52tpgtye00jccn7w8t4zwhxy3b4dpbblds.jpg)

The Marquise Arconati-Visconti (1840-1923) had a considerable influence on the world of art and literature. On her husband’s death, she inherited his entire fortune and began a vast collection of eclectic art, spanning all periods and origins, which was to feed several Paris museums. A great scholar, she also championed the cause of university research, making donations to numerous libraries, prestigious schools and universities.

The Cognacq-Jay couple, best known for their philanthropy and social solidarity work at the end of the 19th century, were also patrons of the arts through their collections of 18th-century works, first exhibited in their luxury Parisian store La Samaritaine in 1925, then moved to the Hôtel Donon in 1990 to create the Musée Cognacq-Jay.

Nélie Jacquemart-André (1841-1912), initially a renowned portraitist, developed an important collection (begun with her late husband) of works of art from all horizons as she traveled the world. She bequeathed her entire estate to the Institut de France, which transformed her two residences in Paris and Chaalis into the Jacquemart-André museums.

During the interwar period, American patrons of the arts began to show a new enthusiasm for safeguarding France’s heritage, thanks in part to the financial support provided by John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874-1960) for the restoration of the Château de Versailles in 1924. John D. Rockefeller Jr., a wealthy American philanthropist, declared his love of France and its art by contributing to the restoration of the Château de Fontainebleau and Reims Cathedral. Through his actions, he influenced many foreign private patrons to invest in the preservation of French and European heritage.

Patrons of the arts in France today...

« Patronage: material support given without direct counterpart on the part of the beneficiary to a work or person for the pursuit of activities of general interest. »

(current legal definition on the french site culture.gouv.fr, translated with deepl.com)

« Patronage: material support given without direct counterpart on the part of the beneficiary to a work or person for the pursuit of activities of general interest. »

(current legal definition on the french site culture.gouv.fr, translated with deepl.com)

The widespread notion of patronage as financial support for an artist made the latter dependent on his patron and protector. Today, the artist is no longer considered to be at the service of his donor, but rather at the service of Art itself. To quote Kandinsky in his 1910 book Du Spirituel dans l’Art, art is seen as an “inner necessity”, a vocational activity in which creation and expression are necessary.

Patronage today can take the form of “financial” patronage, but also “in-kind” or “skills” patronage, where monetary donations, donations of premises or materials, and donations of specific know-how complement each other. We can also distinguish several types of patronage beneficiaries: production patronage (to encourage artists to create), heritage conservation patronage (to safeguard a historic monument), heritage collection patronage (to enrich a museum) and entertainment patronage (to organize shows, exhibitions, etc.).

The French state is not a patron of the arts in the strict sense of the term, but it does support patronage. From the second half of the twentieth century onwards, its actions have focused on supporting the creation and enrichment of national collections, and on facilitating access to culture for as many people as possible: from this perspective, we can still speak of “state cultural patronage”, particularly present since the 1960s with the Malraux and Lang ministries.

The “real patrons” are organized around legal entities (companies, foundations, associations, etc.) and private individuals (wealthy art lovers and major collectors, who are very present in the American model).

But individuals can also, through their involvement, take part in promoting an artist or safeguarding a monument or work of art. They often act out of passion, given their sometimes modest financial circumstances.

Artistic sponsorship legislation in France has evolved considerably since the middle of the 20th century, culminating in the Aillagon Law of 2003 and its successive advances. In addition to clarifying the definition of patronage, these new laws improve the tax regime in certain cases, and in particular allow private patrons to reduce their tax liability according to the amount of their donations made to General Interest organizations only. While not all donors and causes can benefit from this “patronage regime”, all – and especially companies – benefit from an enhanced image.

A few examples...

Marguerite “Peggy” Guggenheim (1898-1979) was one of the 20th century’s greatest patrons and collectors of modern art. A self-taught, independent woman, she is best known for championing a number of then little-known artists in her Guggenheim Jeune gallery, opened in London in 1938, and for the opening of the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in Venice in 1952, exhibiting her entire collection.

Since the 19th century, the Rothschilds, an ancient and wealthy European family of great renown, have donated almost 120,000 works of art to various institutions, including the Louvre and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, with their extensive and eclectic collections (drawings, paintings, sculptures, jewelry, furniture, decorative arts, etc.).

The Sauvegarde de l’Art Français, a foundation created in 1921 by Édouard Mortier (Duke of Treviso, 1883-1946), and the Fondation du Patrimoine, a private organization created in 1996, are both non-profit organizations recognized as being of public interest. They work to preserve and promote French real estate and movable heritage, mainly unprotected as historic monuments, thanks in particular to patronage, public subsidies and participatory funding.

More recently, in 2014, Bernard Arnault inaugurated the Fondation Louis Vuitton, which stages ephemeral exhibitions of major figures in modern and contemporary art worldwide.

A.D.M.I.C.A.L., a non-profit organization founded in 1979 by Jacques Rigaud, promotes corporate philanthropy in favor of culture, humanitarian action, solidarity and the environment.

In 2007, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon was able to welcome a painting by Poussin, The Flight into Egypt, into its collections, thanks to the help of 18 patrons and others, for a total of 17 million euros, and in 2016, Man in a Black Beret Holding a Pair of Gloves by Corneille de Lyon (c. 1530), with the help of the patrons of the Cercle Poussin and, this time, a public subscription of over 1,300 donors.

Restoration campaigns are also participative and interactive: again in 2018, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon launched an appeal for donations from visitors at the cost of an additional euro on the admission ticket to support the project to restore the exterior of the Egyptian sarcophagus of Isetenkheb (c. 664-500 BC).

Our non-profit association Muses & A.R.T. is dedicated to safeguarding our endangered painted heritage through voluntary conservation-restoration campaigns. It has succeeded in surrounding itself with private patrons, individuals, amateurs and anonymous companies, who, through their financial support and donations of skills, have contributed to the restoration and preservation of several painted works to the delight of their owners and the public.

In conclusion...

This concludes our “brief” and non-exhaustive (and somewhat arbitrary) history of art patronage.

The social and economic organization of each era has shaped the contours of patronage, which has constantly evolved while maintaining its original vocation of “support and donations without direct and immediate compensation”. However, the patron is often endowed with indirect, non-material rewards such as fame, prestige, renown, honor, trust…

From the noble support of a benefactor to a weapon of political propaganda, art patronage has left its mark on the history of art as we know it today, and the history of the world too.

At the forefront of the artistic scene, artists and patrons of the arts give each other lines, one needing the other to express themselves fully.

The patron, sometimes a simple donor, and often a buyer or collector, has a considerable influence on the artistic production of his time through his own subjective choices. A work of art, an object, whose creation, whether artisanal or artistic, becomes highly symbolic of a certain power and representation of the “Beautiful” according to the patron’s preferences, is promulgated as a work of art and relegated to memory and history. The “tastes and colors” of a single individual can thus guide the artistic work of an entire era.

« Combien d’artistes (et de génies parfois) ont pu s’épanouir et ou être préservés de l’oubli grâce au mécénat ! Entre l’artiste accaparé par sa création, ou le chercheur qui ne vit que pour sa recherche, et le reste du monde, il faut presque toujours un intermédiaire, que ce soit l’État, une entreprise ou tout simplement une personne. Le mécénat, c’est la rencontre de deux mondes qui souvent s’ignorent, parfois s’attirent et se repoussent en même temps, simplement parce qu’ils ont du mal à se comprendre ; c’est un partenariat : deux partenaires qui cheminent un certain temps côte à côte et vont s’enrichir de leurs mutuelles différences. »

(Debiesse François, Le mécénat, Paris, « Que sais-je ? », 2007 (p.12))

« Combien d’artistes (et de génies parfois) ont pu s’épanouir et ou être préservés de l’oubli grâce au mécénat ! Entre l’artiste accaparé par sa création, ou le chercheur qui ne vit que pour sa recherche, et le reste du monde, il faut presque toujours un intermédiaire, que ce soit l’État, une entreprise ou tout simplement une personne. Le mécénat, c’est la rencontre de deux mondes qui souvent s’ignorent, parfois s’attirent et se repoussent en même temps, simplement parce qu’ils ont du mal à se comprendre ; c’est un partenariat : deux partenaires qui cheminent un certain temps côte à côte et vont s’enrichir de leurs mutuelles différences. »

(Debiesse François, Le mécénat, Paris, « Que sais-je ? », 2007 (p.12))

Sources

Bibliographie

- François Debiesse, Le mécénat, Paris, PUF, « Que sais-je ? », 2007

- Michael Baxandall, L’œil du Quattrocento, l’usage de la peinture dans l’Italie de la Renaissance, Editions Gallimard, 2020 (réed.)

Sitographie

- Encyclopedia Universalis (en ligne) :

- Nathalie HEINICH, Luigi SALERNO, « MÉCÉNAT», Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne], consulté le 24 mai 2022 (URL : https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/mecenat/)

- Nathalie HEINICH, « ART (Aspects culturels) – Public et art», Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne], consulté le 24 mai 2022. URL : https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/art-aspects-culturels-public-et-art/

- Marie-Geneviève de LA COSTE-MESSELIÈRE, « CONNAISSEURS», Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne], consulté le 24 mai 2022. URL : https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/connaisseurs/

- Wikipedia

- https://books.openedition.org/pur/45650?lang=fr (accès libre en ligne depuis 2018 du livre : « La dame de cœur », Patronage et mécénat religieux des femmes de pouvoir dans l’Europe des XIVe XVIIe siècles, colloque sous la direction de Murielle Gaude-Ferragu et Cécile Vincent-Cassy, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016)

- https://www.coupefileart.com/post/le-mécénat-une-question-inchangée-depuis-la-renaissance

- https://www.carenews.com/fr/news/5-femmes-mecenes-et-engagees-qui-ont-marque-l-histoire

- https://www.museecognacqjay.paris.fr/le-musee/histoire-du-musee

- https://www.chateauversailles.fr/decouvrir/histoire/grands-personnages/john-rockefeller-jr#versailles-tresor-international-de-la-france

- https://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/fr/fondation

- https://www.sauvegardeartfrancais.fr

- https://www.fondation-patrimoine.org

- https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Mecenat/Qu-est-ce-que-le-mecenat