From the February 2024 Newsletter. Would you like to receive it by e-mail? Join Muses & A.R.T.!

Or request it via our contact form!

Failed restorations

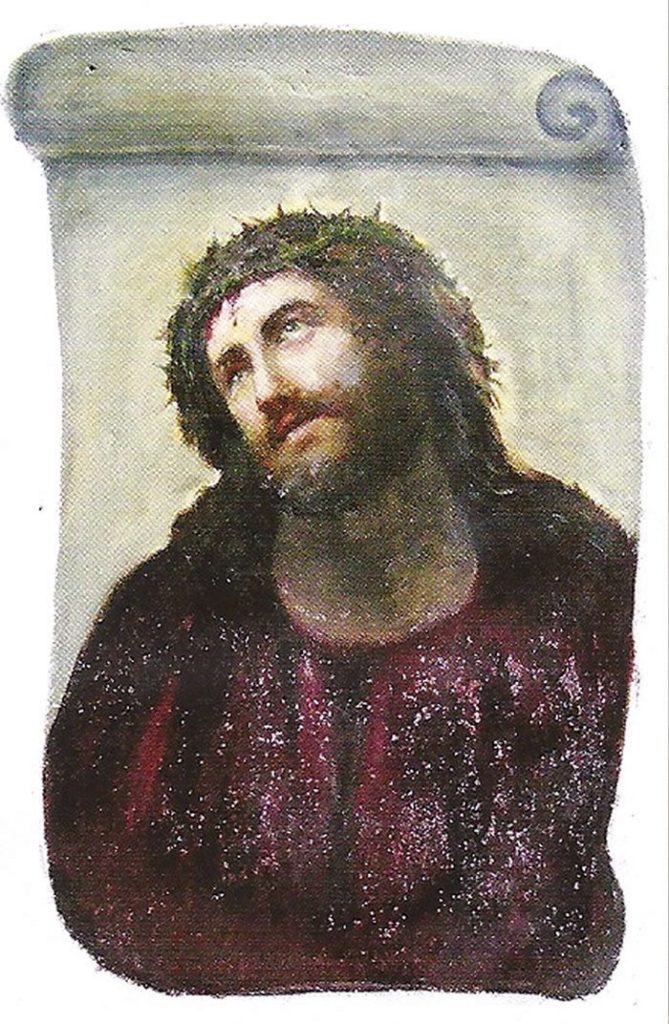

Who among us hasn’t heard of that poor Spanish Christ disfigured by a so-called “restorer”? Borja’s Ecce Homo is one of the worst restorations in the history of art.

Photo BEFORE / AFTER can be seen on The New York Times, with the visual of the disastrous restoration.

In 2012, this late 19th-century painting – Ecce Homo, a sober portrait of Christ painted directly on the wall of a church in Zaragoza – was restored by an octogenarian amateur…

Although the work was showing signs of wear due to humidity, the artist’s intervention gave Christ a major pictorial metamorphosis. The result is a deformed face that looks more like a monkey than a man. The restoration went viral on social networks, and it has to be said that the financial repercussions of this scandal for the Borja municipality more than compensated for the “artistic” damage caused by this botched restoration. In fact, the number of tourists visiting the town rose from 6,000 to 57,000, and the money raised for the church visiting the fresco was used to finance a retirement home.

In 2022, a work after Murillo in Valencia, Spain, was entrusted to a furniture restorer. The delicate face of the Virgin has been transformed into a childish figure.

What can we deduce from this?

While it’s true that Spanish law allows people to embark on restoration projects without the necessary skills, it must be remembered that the conservation-restoration of cultural property is a serious, technical profession in which there’s no room for improvisation.

However, “botched” restorations have been going on for centuries in many countries. Unfortunately, the loss of many works of art, even masterpieces, is deplored.

So, why?

If we take a brief look at the history of restoration, we know that restoration as a philosophical notion is as old as artistic creation. Once a work of art has been created, it undergoes a process of degradation of its constituent parts, leading to direct human intervention.

In the Middle Ages, if a work of art was no longer up to date, or if it showed signs of deterioration, artists would repaint it totally or superficially. A painting with flakes was copied and discarded.

The Madonna and Child by Coppo Di Marcovaldo (1225-1276), painted in Siena (Basilica San Clemente in Santa Maria dei Servi) in 1261, was repainted a few decades later by one of his pupils. Thanks to X-rays, the Madonna’s true face can now be seen again.

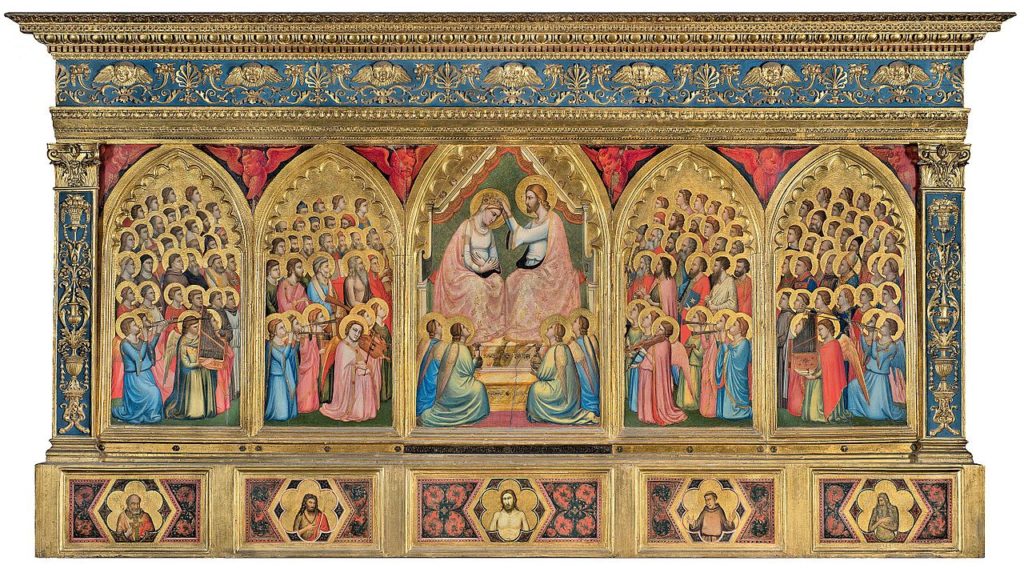

Or Giotto’s altarpiece (1266-1337) “The Coronation of the Virgin”, whose upper section has been cut to fit.

Decorative concerns take precedence over historical respect.

The birth of a profession

The 18th century saw the birth of the restorer’s profession, and a distinction was made between the painter’s and restorer’s work. The profession appeared simultaneously in France and Italy. But with the emergence of new restoration techniques such as transposition, restorers became overzealous, and many major works were lost during restoration operations. These transposition procedures made it possible to change an initial support when it showed significant pathologies. The actions taken to carry out these operations largely contributed to the loss of priceless works.

In 1750, Robert Picault’s workshop transposed Andréa Del Sarto’s La Charité, painted in 1518, using mercury or nitric acid to “unstick” the paint layer from its wooden support and place it on a new support, a canvas. Today, the work, weakened by these treatments, continues to present new pathologies: loss of the properties of the painting’s constituents, causing displacement, loss of material and new cracks.

This method was soon abandoned by scrupulous craftsmen, but survived among others.

Workshop secrets, techniques not shared, are at the root of the destruction of works of art.

We had to wait until the end of the 19th century, or even the 20th century, to see, through the progress of chemistry and the birth of laboratories, a different artistic consciousness.

The birth of a code of ethics

With the development of museums and academic collections, the status of conservator came into its own. The rules of the profession emerged, and the restorer was no longer to be a creative artist, but a practising technician at the service of the work.

A text written in 1963 by Cesare Brandi, then Director of the Central Restoration Institute in Rome, laid the foundations for modern Restoration: Brandi’s demonstration was based on the fact that a work of art is a product of human creation, but one that differs profoundly from all others.

The difference between the work of art and the ordinary object lies not in the materials used or the technique, but in the recognition of this creation as a work of art. This is where the difference between repair and restoration comes in.

After various charters and codes of deontology, the ECCO code was born in 1993 and adopted by the national assembly on March 1, 2002 (European Confederation of Conservator-Restorers’ Organization).

The general principles stipulate that the conservator has a duty to preserve cultural assets for the benefit of future generations, whatever the object or cultural asset to which society attributes an artistic, historical, documentary or aesthetic value… and not, as many think, to reduce the work to a mere market value.

The conservator-restorer therefore has a responsibility not only to the owner of the work, but also to the work itself. They must contribute to the understanding of cultural assets, while respecting their aesthetic and historical significance.

In short, the conservator-restorer must work in accordance with these principles. He must limit his intervention to what is strictly necessary, giving priority to the conservational aspect of the work rather than its aesthetic aspect.

He must also seek to use products, materials and processes that correspond to the current level of knowledge and that will harm neither the work nor the environment, materials or techniques that must be stable and reversible. This excludes many techniques used by restoration neophytes, such as acrylics and oils, which are not reversible.

Finally, the conservator-restorer can refuse any request that seems contrary to the rules or spirit of the code of ethics, such as intervening on a signature, or improperly retouching areas that are difficult to read but present in fragments.

So why are so many works still exempt from the rules of conservation?

If today we want the restorer’s work to remain reversible, we must remember that varnish removal is an irreversible operation, as are many acts of restoration to varying degrees, and that the public has little or no warning…

Dangers persist when technological tools are used incorrectly or incompletely, due to a lack of experience in the use of these techniques or a lack of communication around preliminary studies. All these factors contribute to a certain form of obscurantism, which can lead to restoration rather than conservation.

- Restoration and conservation are, after all, fairly recent philosophical notions, and intervention choices are often delicate and pose limits to intervention. For example, the conservation and restoration of heritage human remains in museums raises ethical, social and cultural questions, even if the interventions are based on deontological principles and doctrines. The ECCO code states that the conservation and display of these “human remains” must be carried out in accordance with the interests and beliefs of the ethnic or religious groups of origin, while respecting human dignity.

- Cesare Brandi, in his book Théorie de la Restauration, suggests that “restoration is permanently drawn towards empiricism”, “that the danger is perhaps even greater than before, because the cultural industry that exploits the tourist appeal of works of art takes precedence over the rigor and demands of restoration”. It’s true that the restoration of L’Ecce Homo, a painting in the Church of the Sanctuary of Mercy in Borja, a real pictorial failure, was a real tourist success for the town, and nothing is being done today to carry out a real ‘de-restoration’ campaign”. (Cesare Brandi, Théorie de la Restauration, 1963, French translation by Colette Déroche, Edition du Patrimoine, Monum, Paris, 2001, p.21) (french citation translated with Deepl.com)

- In 2003, British art historian and restorer Sarah Walden published The Ravished Image. As quoted in the introduction to the reports of the french Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques, “Sarah Walden […] does not hesitate to write: ‘the scale of restoration of paintings over the last fifty years is unprecedented, both in terms of the number and the extremism of the methods employed, which range from the inadequate to the totally irresponsible. The author goes on to warn the reader: “If Titian or Leonardo da Vinci were to venture into one of our great museums of painting today, how would they react? […] They would be philosophical about the effects of time on oil paint or canvas, but horrified by the ravages inflicted by man on their works”. (Report on techniques for restoring works of art and protecting our heritage from the ravages of ageing and pollution, (Introduction) by Mr Christian KERT, Deputy, Assemblée nationale n°3167 and Sénat n °405, June 15, 2006, translated from french with deepl.com)

- The french Association pour le Respect de l’Intégrité du Patrimoine Artistique (ARIPA) (Association for the Respect of the Integrity of Artistic Heritage) debates the actions undertaken on major works and denounces the problems. One example is the restoration of Veronese’s masterpiece The Pilgrims of Emmaus, painted in 1560. A fundamental restoration was undertaken in 2003-2004 by the Louvre and the C2RMF. As the restoration did not meet the desired objectives, it was resumed in 2009 without further success. The association had highlighted abusive retouching altering the character’s expression (nose redone, mouth stretched and lower face puffed up, eyebrow absent…). You can consult the file on aripa-revue-nuances.org

In conclusion...

In conclusion, the profession of conservator-restorer remains complex, even when qualified, always oscillating between respect for history and intervention. If he is not a professional, the restorer must refrain from any intervention in the name of respect for the artist and the work. If he is, his responsibility is engaged, and his mission consists of carrying out a precise examination of the work’s constituent elements and their pathologies, in order to determine the direct (on the work) or indirect (on the work’s environment) actions to be undertaken on the cultural asset, in order to delay its deterioration, not forgetting to “rethink the methodology” and develop restoration procedures for a safe and measured practice.

Sources

Bibliography

- Cesare Brandi, Théorie de la Restauration, 1963, Traduction française de Colette Déroche, Edition du Patrimoine, Monum, Paris, 2001

- Sarah Walden, Outrage à la peinture : ou comment peut la restauration, violant l’image, détruire les chefs-d’œuvre, Traduction française de Christine Vermont et Roger Lewinter, Editions Ivrea, 2003

Sitography

- On the Ecce Homo of Borja : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecce_homo_(Elias_García) OR https://www.lemonde.fr/big-browser/article/2016/08/16/les-retombees-inattendues-de-la-restauration-completement-ratee-d-ecce-homo_4983570_4832693.html OR https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/24/world/europe/botched-restoration-of-ecce-homo-fresco-shocks-spain.html OR https://www.connaissancedesarts.com/musees/restauration/les-12-restaurations-les-plus-ratees-de-lhistoire-de-lart-11142535/

- On the copy of the Immaculate Conception of the Escorial after Murillo in Valencia : https://www.connaissancedesarts.com/musees/restauration/une-vierge-dapres-murillo-defiguree-par-une-restauration-11141693/#:~:text=Le%20drame%20s%27est%20d%C3%A9roul%C3%A9,%C3%A0%20un%20restaurateur%20de%20meuble.

- ECCO, European Confederation of Conservator-Restorers Organisations (Texts in english) : https://www.ecco-eu.org/home/ecco-documents/

- Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques, Rapport sur les techniques de restauration des œuvres d’art et la protection du patrimoine face aux attaques du vieillissement et des pollutions, Par M. Christian KERT, Député, Enregistrement Assemblée nationale n°3167 et Sénat n °405, le 15 juin 2006 : https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/12/rap-off/i3167.asp

- Association pour le Respect de l’Intégrité du Patrimoine Artistique (ARIPA) : https://www.aripa-revue-nuances.org