From the Newsletter of June 2021… Would you like to receive it by e-mail? Join Muses & A.R.T. !

Or ask it for free via our contact form !

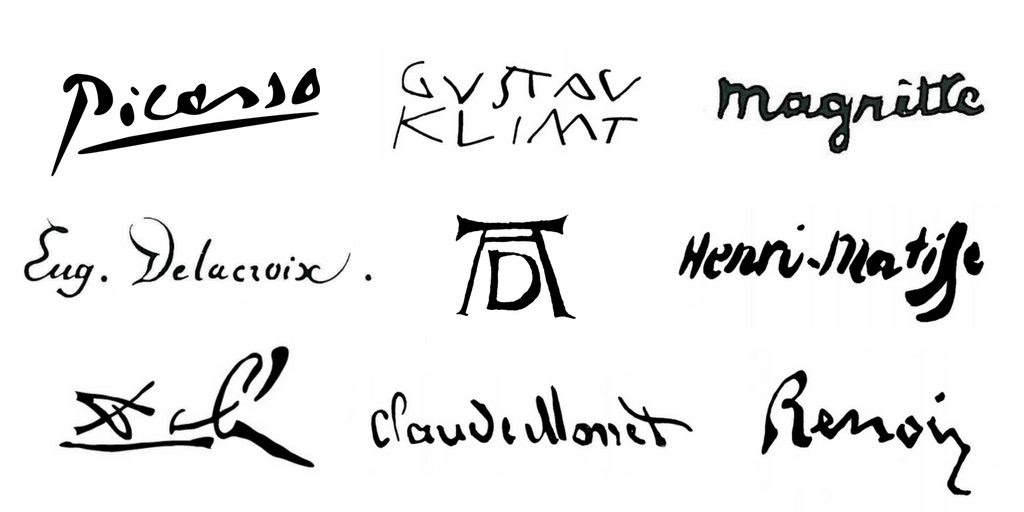

The signatures of paintings

after La Griffe du Peintre, by Charlotte Guichard

Why do artists sign their works ? Have they always done so ? How did the name carried by this signature become a symbol, a commercial value ?

The signature has taken on different meanings throughout the history of art, but it is interesting to note that it was never made compulsory by the guilds or by the Royal Academy of Painting.

The origins of the signature in Painting

The material traces of “signatures” are fragile and may have disappeared with the modification of the original supports and formats of paintings. For this reason, it is difficult to estimate the number of painters who signed their works.

Placing one’s name on a canvas or a wooden panel is a tradition that goes back to antiquity, but we note that most of the painters of the Middle Ages and the Classical Age signed little or not at all. It is from the first third of the 18th century that signatures became less rare and gradually became a “visual convention”.

The term “signature” to describe the affixing of a name at the bottom of a painting only appeared at the beginning of the 19th century with the museographic literature.

During the Renaissance and the Classical Age, the word did not exist in the field of art. The treatises and dictionaries speak rather of “mark”, “monogram”, “figure”, “name” and say nothing about the life of the artists nor their works.

In the 18th century, the signature of painters experienced a great expansion but the Encyclopedia still defines the term “sign” as the mere fact of putting one’s name at the bottom of an administrative document.

The inscription of the name in the painting is also due to legal practices. The recognition of copyright and intellectual property for writings was not born until the beginning of the 18th century with the end of the absolute monarchy. The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture recognized at the same period a first form of copyright by authorizing engravers to reproduce and sign only their works. The name becomes the property of the artist whereas the Royal Academy previously had a privilege on all productions.

What does the signature mean from Antiquity to the Renaissance ?

Since ancient times, the name of the artist has been a marker of quality. The painters put inscriptions on their paintings which allowed them to be identified as the authors of their works. The “faciebat” (“made by..”) of the Middle Ages was followed by the “me fecit” of the Renaissance.

For a long time, the signature in painting remained a workshop mark, a certificate of quality and style of the master, of the excellence of the technique and the quality of the materials. One learned little from the artist himself.

In the Renaissance, it was also common for a master to put his name on a painting that he had not completed. The signatures did not mention the anonymous hands of the workshops, sometimes only the names of collaborators.

Until the Classical Age, a work was considered original when it was a new creation of the painter. The signature of the workshop master made him responsible for the invention, not necessarily for its realization.

The painters of this period used the new conventions of printing for the design of their signature.

Bellini abandons his known signature in capital letters for a new one in cursive letters typical of humanist circles.

The same goes for Dürer, who worked on the signature of his paintings and wrote a book for artists on the codification of printing fonts.

In Venice, the signature is clearly visible in the painting. It is no longer only inscribed in the frame, but sometimes appears on a cartel painted in the composition and becomes a mark of provenance while production explodes.

Titian perpetuates this Venetian usage but he “places” himself in the painting by putting his signature in remarkable places. In the painting of the “Bacchanal of the Adrians” the artist’s name can be read in the neckline of the female figure.

Cranach’s studio mark was handwritten but not autographed. This explains why there is a great diversity of signatures with the snake.

At the beginning of the 17th century in Europe, an artistic literature appeared on the attribution and authentication of works of art and which spoke of the relationship between the original and the copy.

In the inventories made after death the name of Bruegel appears more than two hundred times, without ever making the difference between Peter the Elder, Peter, Peter the Younger, Jan the Older… between the workshop and the copyists. It is the mark that still counts.

But at the same time, Rubens, in the context of an exchange between antique statues and several of his paintings, notifies in the list of his works those which are by his hand and those executed with the collaboration of another, as well as the paintings made by his most advanced assistants and then retouched by him.

Some examples of “signatures” in the Classical Age

In the 17th century, painters who signed were still rare and essentially Italian or Dutch.

Vermeer signed with letters set in the manner of a monogram.

Rembrandt, who signed his entire work, used a cursive signature. He chose to use his first name like the Italians Raphael, Michelangelo and Titian and opted for a clever calligraphy. The letter B in his name written in Gothic font became an element of recognition.

Unlike Rembrandt, Rubens signed only sixteen of his paintings, while his workshop, organized like a factory, produced a very large number of works.

Caravaggio could stage his signature as he did in “The Beheading of St. John the Baptist” by making it in the red paint that forms the blood of the martyr.

The practice of signing is rarer among French painters of the 17th century.

However, some of them signed more often than their colleagues and signed in cursive letters in the heart of their works, not in the margins.

Le Sueur signed only one of his paintings, going over it twice, as the traces of repentance show. But it was a work exhibited on the forecourt of Notre Dame and visible to all, at a time when paintings were not in the public space.

Claude Le Lorrain, who saw his paintings multiplying, used his signature intensively to fight against forgers. He wrote a “catalog”, preserved in the British Museum, with the drawings and descriptions of his paintings, the sponsors and dates of realization.

De la Tour signed his painting “Saint Thomas” before it was exported to Paris, but the signature was later erased.

The fear of the work’s distance and the loss of its creator, the desire to make himself known to a distant clientele and not only to the Lorraine elites no doubt explain the signature on the works exported by the master.

Transformation of the art world and autograph signature

The use of the signature in painting increases from the 18th century and multiplies in the second half. It became an autograph signature : the name of the artist written by his hand.

This evolution follows the market of the painters which in Paris widens and leaves the narrow circles of the princely orders and the rich elites.

The world of art was being recomposed. A new market opens for easel paintings, more active with the organization of public exhibitions by the Royal Academy, the institutions, the Louvre Salons.

The latter offered the public booklets that made room for proper names written in capital letters. The catalogues raisonnés multiplied. The value of the painting is concentrated in the signature, a real cult of the artist develops.

One sought autographed paintings that express the artist’s performance in a gesture and know-how that are his own. This form of signature is both a trace of the hand and an artistic gesture, which makes some people say : “We buy names, not works”.

The pieces of reception for the Royal Academy (works made for the entrance in the institution) follow the same evolution and begin to be signed only in the middle of the century. It became a convention for painters who stayed at the French Academy in Rome to place their names in monumental letters in the architectural elements of their paintings. This is the case of Hubert Robert.

With all these evolutions, the signature will take new forms : disappearance of the Latin inscription preceding the name, affixing the signature on the face (the lining making disappear the back inscriptions), use of the cursive writing more personal and more direct than the letters of printing, often in bottom on the right of the painting.

L’exemple de Chardin

In the history of the signature in the 18th century, Jean Siméon Chardin occupies a particularly remarkable place.

This painter of the Enlightenment signed a lot, much more than his contemporaries (2/3 of his paintings) with a great awareness of the value of his art, of the fame of his name.

Chardin very quickly found his signature, which never changed once the first years had passed. It is immediately recognizable : the same regular large letters applied, the same ochre color as the domestic objects represented in his paintings. It evokes his artistic universe.

The signature does not stand in the margin of the painting but is found everywhere, sometimes even in the center of the composition and is visible. “It is not read, it is seen”.

The name is drawn with a brush but with light touches of white (a mixture of pigments and chalk powder, a specialty of Chardin) and gives the effect of an engraving in the stone especially if the signature is found in an entablature, a wall of the composition.

In other of his paintings it is the point of a knife that designates the signature.

Diderot uses the word “griffe” (claw), rarely used in the field of painting, to describe Chardin’s way of painting which is in itself a signature. He writes : “Chardin only needs a pear, a bunch of grapes to sign his name… and woe betide the one who does not know how to recognize the animal by its claw”.

Chardin is also at the origin of a vast movement of reproduction of his works by the engraving. He took care that each of his reproductions bore his name and thus aroused desire.

Nattier, on the other hand, made copies of his portraits but only signed the first ones that he considered to be the originals.

Boucher built his reputation and shaped his artistic identity like Chardin by disseminating his work through prints. He created his own style with a pastoral repertoire and tirelessly repeated motifs.

Surprisingly, Watteau, a recognized painter during his lifetime, never signed his works. Known by the very closed circle of his patrons, he undoubtedly intended his paintings for his followers and protectors.

Fragonard who painted for small circles had a very sketchy touch. The articles criticizing this particularity of the artist never gave his full name but shortened it. His name was thus “sketched” like his paintings… which he ended up signing for some “Frago”.

Sometimes illegible, his signature merges with the pictorial matter. Fragonard was amused by the image that his contemporaries gave him.

Hubert Robert, like many artists who stayed in Rome, inscribed his name on the architectural elements of his compositions by Italianizing or Latinizing it.

A very good Latinist, he could add to his name traditional or invented inscriptions.

Hubert Robert put his name everywhere on his paintings but also placed “a draftsman” in the middle of his compositions thus marking his paintings with his presence.

It is amusing to note that the artist, during his stay in Italy, left his name off his canvases. There are at least two graffiti left by the painter in the vicinity of Rome : on the walls of the Farnese Palace and on the ancient vault of the library of Hadrian’s villa in the Colosseum of Rome !

Hubert Robert, like many artists who stayed in Rome, inscribed his name on the architectural elements of his compositions by Italianizing or Latinizing it.

A very good Latinist, he could add to his name traditional or invented inscriptions.

Hubert Robert put his name everywhere on his paintings but also placed “a draftsman” in the middle of his compositions thus marking his paintings with his presence.

It is amusing to note that the artist, during his stay in Italy, left his name off his canvases. There are at least two graffiti left by the painter in the vicinity of Rome : on the walls of the Farnese Palace and on the ancient vault of the library of Hadrian’s villa in the Colosseum of Rome !

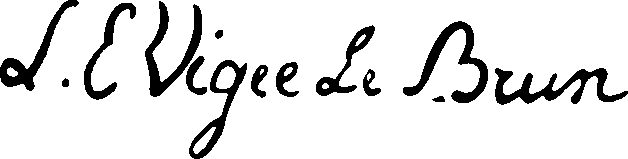

The name of the women

Female careers in painting were not uncommon in the Modern Age although it was particularly difficult for a woman painter in the 18th century to make a name for herself.

Women were legally minors with the exception of unmarried women over 25 and widows who could only sign their paintings in their own name. The signature of married women painters was subject to that of their husbands, because when they got married they lost their legal capacity.

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun was reminded of this minority status when she presented herself to the Royal Academy. She could not be admitted because she was the wife of a painting merchant. Only her status as a protégé of the queen and her talent worked in her favor.

Nevertheless, these women developed strategies to consolidate their careers.

Elizabeth Sophie Cheron signed her engravings by keeping her surname and reducing her married name to initials.

At the end of the following century, Anne Vallayer-Coster signed her paintings, flowers and miniatures, according to the changes in her marital status. She affixed her unmarried name for her first works and added her husband’s name after her marriage.

The female signatures also bear witness to political developments.

After the Revolution and during the first republic, aristocratic marks in front of names were removed, women became citizens and appeared under their married name.

For example, Marie Guilhelmine-Benoist (1768-1824) who was called successively : Mlle Leroux de Laville, Mlle Laville, Citoyenne Laville femme Benoist, Citoyenne Benoist née Laville, pupil of David, Madame Benoist pupil of M. David.

It is difficult to impose oneself with a name that keeps changing !

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who, like all married women without legal capacity, did not receive any dividends from her work, consistently noted her name at the bottom of all her works. Her signature, often engraved with the tip of a penknife as if scratched, and the care taken with the calligraphy, which testifies to her education, were particularly important marks at a time when women were often suspected of not having created the paintings bearing their signatures themselves.

The suspicion in the art world was that they were often daughters, sisters or wives of painters, and that their paintings were of autograph quality. It concerned all women up to the reception pieces at the Academy.

Women painters often used the conventional formula “painted by Mrs…” from the classical pinxit or faciebat but only the performance of the gesture could make them be recognized as artists.

Diderot wrote: “to believe in a woman’s talent, one must have seen it” !

In order to answer this suspicion, several women candidates for admission to the Academy used strategy by painting several of their future judges on the spot and thus demonstrated their talent.

As these examples from the 18th century and many others from Antiquity to the Classical Age show, artists were able to take liberties in signing their works, sometimes circumventing and playing with the conventions of their time. For all that, the signature remains a marker of its time, of the interest given to the Painting. It tells us a lot about works, artists and societies in Europe…

To go further...

La griffe du peintre: la valeur de l’art (1730-1820), book by Charlotte Guichard, the main source of our article, but only avalaible in french…

“Comment le nom de l’artiste est-il devenu un élément clef de la valeur symbolique et commerciale des œuvres ? Pourquoi les peintres signent-ils leurs tableaux ? C’est à Paris, entre les années 1730 et 1820, que se déploie cette enquête novatrice et richement illustrée. Salons et expositions publiques, ventes aux enchères, musées : les institutions artistiques modernes imposent le nom de l’artiste au cœur des mondes de l’art. Critiques, catalogues, cartouches et cartels lui accordent désormais une place essentielle. Un contemporain constate, avec dépit, que les amateurs achètent “des noms, et non plus des œuvres ?”“–Page 4 of the cover